SEOUL, October 15 (AJP) - "When I broke the window and stepped inside, I realized I had stepped on a dead body."

Lee Chang-seok, a 19-year veteran firefighter, still remembers one of the first fires he responded to in his first year on the job. The fire had already spread through the building—a restaurant below and a home above—and the windows were sealed shut by signboards.

"They tried to escape through the window," he recalled. "But the signs blocked them. A mother, her daughter and a tutor—all found dead by the window."

The memory of that night—the feel of what was under his boots—never left him. Even years later, the scenes witnessed return without warning.

Since the Itaewon crowd crush in 2022, which killed 159 people during Halloween festivities in Seoul's Itaewon, trauma among South Korea's first responders has drawn growing concern. Two firefighters who responded to the Itaewon disaster took their own lives this year, reigniting questions about the country's mental-health safety net for those who rush toward danger.

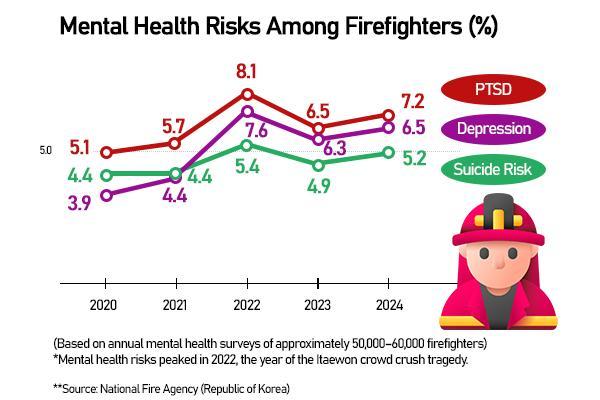

A National Fire Agency survey shows that 7.2 percent of firefighters were at risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 5.2 percent showed suicide risk last year. Yet many remain reluctant to seek help.

Police officers face similar struggles. Between 2020 and 2022, the number treated for depression rose by 67 percent, while PTSD treatments increased nearly 50 percent, according to the National Police Agency and the National Health Insurance Service. National Assembly records show that between 2018 and 2022, at least 105 officers took their own lives, with mental health issues cited as the cause in 44 cases.

Voices from the Field

Firefighters like Lee say the emotional toll of the job hides behind a culture of restraint.

"There's a general perception in our society that getting therapy means you're weak," he said. "It's the same among firefighters—but it carries even more weight for us. Our team leaders give orders that put us inside burning buildings, so they avoid showing any sign of weakness. That mindset runs deep.”

Inside the firehouse, colleagues talk about operations, not emotions.

"We only talk about it with colleagues who were at the scene," Lee said. "We don't tell our families or those who weren't there. It's too painful, and we don't want them to imagine it."

For many, coping becomes a personal effort. Lee spends weekends camping or working out, exhausting himself so sleep will come more easily.

Institutional Reality

Despite years of discussion, South Korea's safety-and-rescue agencies still lack a consistent system for mental-health care.

The National Fire Agency runs Healing Centers and Mobile Psychological Support Units, while the National Police Agency operates Trauma Recovery Clinics.

But staff shortages and brief, irregular counseling leave many responders without proper care. One counselor may be responsible for hundreds of personnel, and sessions can be as brief as 20 minutes every few months.

"PTSD isn't something you treat every three months," Lee said. "You need follow-up care, sometimes medication, and a real treatment system. Not just 20 or 30 minutes of talk."

Every firefighter who attended a major disaster—such as the Itaewon crowd crush or the Muan airport accident that killed more than a hundred people—is required to complete post-incident counseling sessions, but there is still no legal mandate for continued treatment.

System Gaps

Other countries have moved faster to institutionalize mental-health protection for first responders.

In the United States, more than half of states now recognize PTSD as a work-related injury, ensuring full medical coverage and compensation for firefighters and police. The United Kingdom runs the nationwide Blue Light Program, offering free, confidential counseling and resilience training across all emergency-service branches.

South Korea, by contrast, still treats trauma support as a discretionary service rather than an entitlement.

"Abroad, PTSD is acknowledged as a professional risk," said Oh Eun-kyung, a counseling psychologist and professor at the Air Force Education and Training Command.

She said the Fire Agency and the Police Agency operate counseling and trauma centers, but their services remain limited compared with other countries.

"Firefighters live with chronic exposure to crisis," Oh said. "They need regular check-ups, not one-time interventions. Prevention, early response, and long-term management should all be part of one cycle."

Cultural Barriers

Experts say South Korea still struggles to break the stigma surrounding mental health.

"Many first responders still think seeking help means they've failed to endure," Oh said. "But trauma is not weakness—it's a natural human response to extreme stress. They need to be told that healing is part of duty, not a sign of fragility."

She proposed a nationwide roadmap covering an entire career cycle, from recruitment to retirement, including regular psychological check-ups, anonymous counseling options, and partnerships with mental-health hospitals for specialized treatment.

Lee believes post-disaster counseling should be mandatory, noting that delays of weeks or months in getting a counseling appointment often render treatment meaningless.

"If someone finally decides to see a psychiatrist or counselor, and then has to wait four to six weeks for an appointment, that window is already lost," he said.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.