SEOUL, November 13 (AJP) - Divorce is no longer a social taboo in traditionally conservative South Korea, with a steady stream of reality shows and court dramas themed around marital breakups — and real-life billion-dollar splits among chaebol families such as SK Group and Smilegate drawing intense public attention.

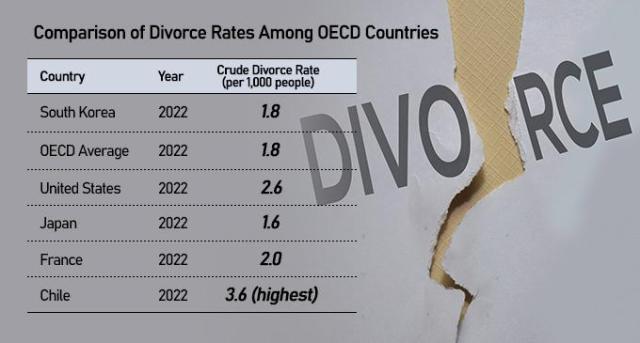

But little about divorce is romantic for ordinary couples. Korea’s divorce rate stands at 2.1 per 1,000 people — roughly half the global average of four — yet litigation costs have soared and disputes have grown more combative as dependent spouses push for a bigger share of assets.

The latest case to dominate headlines involves Smilegate founder and chairman Kwon Hyuk-bin, whose net worth is estimated at 8 trillion won ($5.8 billion). His wife is reportedly seeking half of Kwon’s full stake in the unlisted gaming company.

“The divorce of the century” between SK Group Chairman Chey Tae-won and his ex-wife Roh So-young also returned to the spotlight last month after the Supreme Court overturned a lower court ruling ordering Chey to pay 1.38 trillion won ($1 billion).

The eye-popping numbers have captivated the public, but family lawyers caution that these cases are outliers in a system where most settlements are far smaller — and where proving financial or domestic contribution remains notoriously difficult.

“People see these chaebol divorces and assume they can claim half. We’re already seeing clients ask whether they too can receive this amount,” said Lee Eun-hae, a divorce attorney at VROIN Law Firm. “In reality, it’s very rare. Courts divide assets based on provable contribution — and if one spouse wasn’t engaged in income activities, a 50:50 split almost never happens.”

Under Korean law, marital property is divided according to each spouse’s contribution to wealth accumulated during the marriage. Non-monetary efforts such as childcare and household labor are recognized but still undervalued in practice, Lee added.

“For non-working spouses, it’s very hard to quantify household or emotional labor,” she said. “Most cases end around a 6:4 or 7:3 ratio, depending on the marriage length and whether there are children involved.”

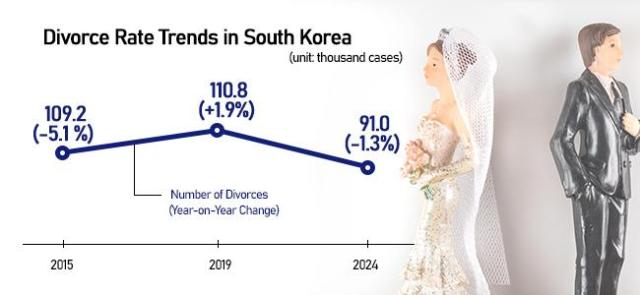

Although Korea’s official divorce rate has dipped in recent years, experts say the trend partly reflects delayed marriage registrations rather than fewer separations. Lawyers and sociologists note that younger couples are more pragmatic — marrying later, divorcing sooner, and often handling breakups discreetly without going through formal litigation.

“Younger generations view divorce less as a stigma and more as an option,” Lee said. “Some couples even end their marriage quietly without going to court.”

As wealth becomes increasingly concentrated, legal experts say Korea’s family-law framework must evolve to reflect modern partnerships — including fairer recognition of unpaid domestic work and clearer valuation standards in high-asset marriages.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.