The 52-year-old social worker swiped it with ease, as she does nearly everywhere she shops, commutes, and eats. “I get 10 percent back every time I charge it,” Kim said, sipping an americano from a seniors’ cafe where a cup costs just 1,100 won, or about 81 cents. “It’s accepted at my office cafeteria, the supermarket down the road — pretty much anywhere I need to go in a day.”

The card Kim carries is a version of a growing number of prepaid regional vouchers, issued by municipalities across South Korea. While use is limited to designated local businesses — typically mom-and-pop shops with annual revenues under 3 billion won — the incentive is simple: small discounts for consumers, and a boost in foot traffic for local merchants.

Now, what began as a grassroots policy experiment has become a centerpiece of the Lee Jae Myung administration’s stimulus strategy.

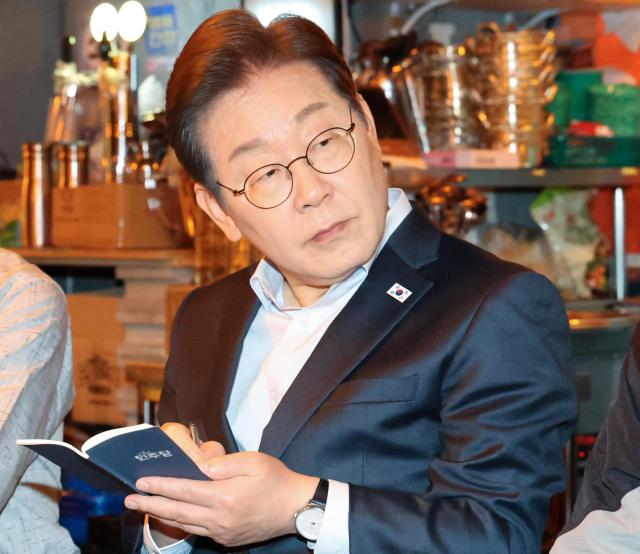

On July 3, President Lee stood before a crowd at Cheong Wa Dae, the former presidential compound in Seoul, pledging that the government’s prepaid voucher program would help “reignite domestic demand” and offer a financial lifeline to small businesses battered by slow growth.

The scale of the initiative is significant. A second supplementary budget passed by the National Assembly just a day later earmarked more than 12 trillion won ($8.7 billion) for the distribution of vouchers — roughly 40 percent of the entire 32 trillion won package. The rollout will begin July 21, with benefits structured across income brackets.

The administration is banking on a familiar formula. As mayor of Seongnam City, Lee launched a similar local voucher system in 2016, handing out vouchers to residents in a bid to strengthen local commerce.

A subsequent report by the Bank of Korea found that Incheon’s consumption rose by 3.6 percent between May and December 2019 after voucher adoption, compared with just 0.1 percent in the months before. The bank concluded the program “positively contributed to stimulating local consumption.”

Still, Lee acknowledged that outcomes remain uncertain. “While we can estimate the effects, nothing is guaranteed,” he said. “We made this decision after taking into account the fiscal outlook, debt, and broader economic conditions.”

Experts, too, are divided. The Korea Development Institute, a state-run think tank, said in its July economic outlook that the second budget could help stabilize economic momentum, unlike the first, which was narrowly targeted.

“Since e-commerce has become the norm, voucher injections can definitely support brick-and-mortar stores,” said Lee Eun-hee, a professor emeritus of consumer science at Inha University.

A recent survey by Korea Credit Data found that more than half of small business owners — 53 percent — had “very high expectations” for the policy.

But there are caveats. “Older people often struggle to understand how to use these vouchers,” Professor Lee said. “And crucially, local governments must fund 10 to 15 percent of the total issuance themselves.”

The financial burden has prompted concern in some cities.

On June 24, Daejeon Mayor Lee Jang-woo called on the central government to assume responsibility. “While local vouchers help restore livelihoods, if this is a government-led policy, the government should foot the bill,” he said.

Some critics argue the policy is a short-term fix.

“These are like IV drips — useful in a crisis, but not a cure,” Professor Lee said. She advocated instead for investment in long-term infrastructure like regional tourism and marketplaces that naturally drive spending.

Others take a more skeptical view. Cho Dong-geun, a professor emeritus of economics at Myongji University, said the government should consider tying vouchers to specific uses like food purchases, rather than geographic restrictions.

“If President Lee wants to support people, he should look at why countries like the United States are cautious about adopting local vouchers,” Cho said, referencing programs like SNAP, the U.S. food assistance initiative.

A 2020 study by the Korea Institute of Public Finance also warned of inefficiencies, noting that while local currencies provide “various economic benefits,” they can also generate “multiple expenses and structural waste.”

Back in Hwaseong, Kim Eun-hee isn’t concerned with macroeconomics. To her, the city voucher is simply convenient — and valuable.

“I used to carry three cards: one for work, one for home, one for discounts,” she said. “Now, I just use this one.”

For President Lee, however, the stakes are far greater.

As South Korea’s economy flirts with stagnation, his government is betting big on the belief that small purchases — made locally and with plastic — can fuel a national rebound. Whether that bet pays off may determine the political and economic shape of his presidency.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.

View more comments