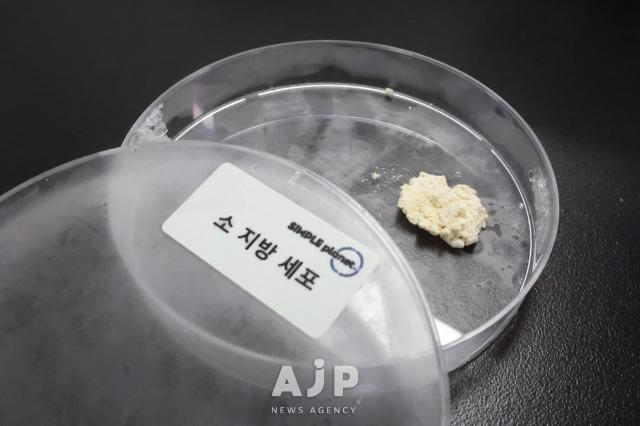

He opens a chilled cabinet and carefully lifts out petri dishes filled with ivory-white clusters.

“These are cultivated animal cells — cow fat and chicken muscle tissue,” Jeong told AJP. “We transform them into protein-rich powders and pastes.”

The company’s "cell-based paste" has no flavor, Jeong explains, and it’s not available for public tasting just yet. That step will require prior approval from South Korea’s Ministry of Food and Drug Safety.

Simple Planet is part of a growing wave of South Korean startups diving into the emerging world of lab-grown meat, or cultivated meat, as a solution to looming global food insecurity.

With the United Nations predicting the global population could reach 10 billion by 2050, the demand for protein is set to nearly double — putting massive strain on existing food systems.

While plant-based meats have long catered to vegetarians and the environmentally conscious, cultivated meat targets a broader audience: meat-eaters looking for a more sustainable alternative without sacrificing the real thing.

Cultivated meat is created by growing animal cells — typically in a nutrient-rich serum — into muscle and fat tissues. The final product, scientists say, is biologically identical to conventional meat.

The same core technology used in regenerative medicine for artificial organs is now being used to grow steaks and chicken breasts.

“The only difference,” says Kwon Yeong-mun, director at meat cultivator TissenBioFarm, “is that one’s meant to heal the body, the other is meant to feed it.”

But here’s the catch: most lab-grown meat on the market still isn’t 100 percent animal-based. Cultured cells often make up just 20 percent of the final product. The rest? Plant-based fillers and binders.

“To make a lab-grown chicken steak, we start with a vegetable protein patty, then add cultured cells and food coloring to mimic real chicken,” Jeong explains.

A Climate-Smart Solution

Why go through all this effort? The environmental benefits are hard to ignore.

Compared to traditional meat production, cultivated meat slashes greenhouse gas emissions, water use, and land consumption. Livestock farming is responsible for roughly 12 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and the push to curb that impact is intensifying as climate change accelerates.

Jeong says his team’s production tests have already shown promising results. Growing 1,000 kilograms of cultured ingredients using a 50-liter bioreactor saved more than 15,000 kilograms of carbon emissions and over 2,200 cubic meters of water.

There are other advantages, too. Lab-grown meat eliminates the need for animal slaughter, sidesteps the risk of food-borne diseases, and avoids the ethical issues tied to factory farming.

Despite the buzz, cultivated meat still faces a steep climb to reach supermarket shelves.

Back in 2013, the world’s first lab-grown burger cost $325,000. But South Korean researchers are closing in on cheaper alternatives.

Professor Joo Seon-tea, who leads the animal science division at Gyeongsang National University, says his startup Orange CAU is nearing commercialization. Their hybrid approach blends cultured muscle tissue with plant protein, which Joo says has passed taste tests and significantly cut production costs.

“We estimate our cultured meat will cost about one-third the price of conventional meat to produce,” Joo says. “Retail prices could land at roughly half.”

TissenBioFarm, meanwhile, says its whole-cut cultivated meat will sell for about 30,000 Korean won (roughly $22) per kilogram — a bargain compared to USDA Prime ribeye, which can run up to $89 per kilogram.

Their secret? A microfiber scaffolding system that mimics the texture and marbling of traditional meat. Kwon explains that the challenge now is scaling up production using large bioreactors to fully infuse those fibers with animal cells and achieve that unmistakable meaty flavor.

Still, most of these products remain in R&D limbo. Regulatory approval is the next major hurdle.

Last month, a South Korean research team made headlines by replicating meat marbling using self-healing scaffolding — a potential game-changer for appearance and structure. But it’s not ready for consumer forks just yet.

“We need Good Manufacturing Practice certification and regulatory approval before anyone can eat it,” says Park Je-young, a professor of bioengineering at Sogang University.

Globally, only a handful of countries — Singapore, the United States, Israel, and recently Australia — have greenlit lab-grown meat for human consumption. South Korea is getting closer. The country amended its regulatory framework in 2023 and issued procedural guidelines in early 2024.

Still, none of the companies have received final approval to sell.

“We cannot disclose how many have applied or when approval might come,” says Sung Jun-hyun, a senior researcher at the National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation. “But as of now, no product has been cleared for market.”

For now, South Korea’s cultivated meat revolution remains confined to labs. But innovators like Jeong are thinking long-term.

“We’re not just building steak replacements,” he says. “Our goal is to deliver high-protein animal products to places where meat is scarce or unaffordable. We want to make cultured bulgogi a reality.”

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.