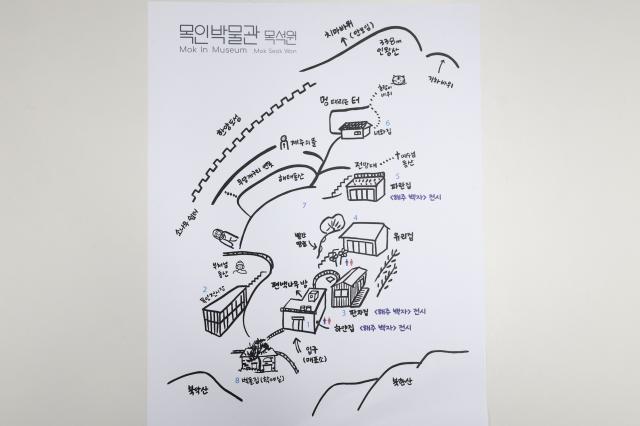

SEOUL, September 05 (AJP) - Tucked away in the quiet residential neighborhood of Buam-dong, Jongno-gu, the Mok-in Museum Mokseokwon feels like a hidden treasure waiting to be discovered. The first sight upon entering is the outdoor exhibition garden, where more than 800 stone carvings are spread across the grounds. Large and small statues stand at every corner, evoking the atmosphere of a Joseon-era stone mason’s workshop. Scholar statues and childlike figures appear to meet the visitor’s gaze no matter which direction one turns. Paths and stairways guide guests to different vantage points, allowing the entire garden to be viewed from multiple angles.

Below the outdoor space, the underground exhibition hall holds the museum’s most striking collection: more than 12,000 wooden figurines. Descending the stairs feels like stepping into another world, mysterious and slightly eerie. Under soft lighting, row upon row of carved wooden figures stand in dense formation, each with a unique face and posture. Some carry objects on their heads, others brandish swords mid-swing, while some appear dressed for a wedding with colorful hanbok and painted cheeks. Many carry playful or satirical expressions, grinning broadly or pulling mischievous smiles.

Among the most memorable displays are the funeral bier decorations. The bier, once used to carry the deceased, is flanked by wooden guardians standing tall and upright, believed to guide souls safely to the afterlife. These were not merely decorative objects but reflections of ancestral beliefs and spirituality. Looking closely, one sees the fine workmanship of past artisans—the carved folds of clothing, the contours of faces, and the details etched into wood. Comparing figurines from different regions highlights distinct local characteristics, adding another layer of interest.

In one corner of the outdoor garden, roof tiles once used in traditional architecture are displayed. Known as maksae giwa, these decorative end tiles were believed to ward off misfortune and invite blessings. Each tile carries its own expressive design, as if ancient guardians once perched on rooftops have gathered here. Another gallery showcases Haiju white porcelain from the late Joseon era, produced in Hwanghae Province. Their simple yet elegant forms glow under subtle lighting, distinct from Chinese porcelain. Especially striking are the pieces adorned with Hangul inscriptions rather than the more common Chinese characters. From painted animals to written phrases, the collection reveals the essence of Joseon-era ceramics.

The rooftop garden offers sweeping views of Seoul’s skyline and the ridges of Bukhansan Mountain. Arranged across the terrace are large traditional jars, some painted, some dented or overturned, glowing softly in the sunlight against the green backdrop. It is a harmonious blend of folk art and natural scenery, offering visitors the feeling of a time slip into Korea’s past at the edge of a modern city.

Leaving Mokseokwon, it is clear this museum holds meaning far beyond its collections. The 12,000 wooden figures, 800 stone sculptures, roof tiles, jars, and porcelains are all time capsules carved and shaped by ancestors. They preserve everyday life, faith, and creativity, carried forward through art into the present.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.