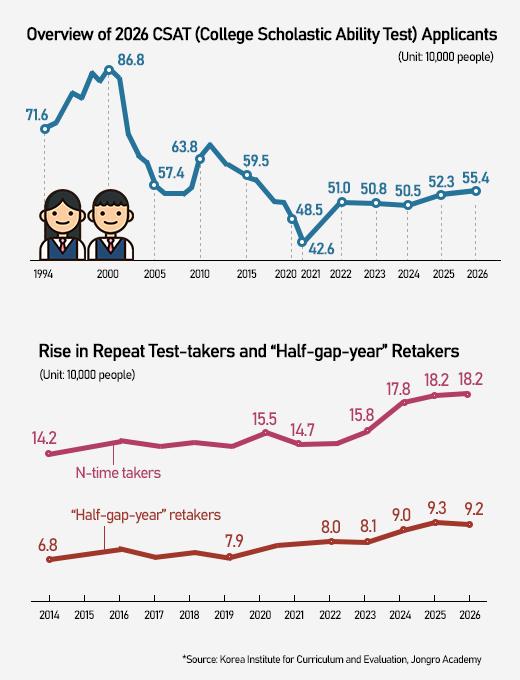

SEOUL, November 11 (AJP) - It's that time of year again in Korea, as the country prepares to solemnly mark "Suneung" — the once-a-year nationwide college entrance exam — on Thursday, when a record 554,174 test-takers will vie for 2026 admissions, clinging to singular hopes despite an increasingly bleak job market for university graduates.

On Suneung Day, Korea enters an extraordinary national ritual. Business hours are delayed to clear roads for anxious applicants; air traffic halts during the English listening section; and churches, temples, and chapels of every faith fill with parents and grandparents praying for a smooth, error-free test.

Whether or not a household includes a test-taker, the entire country slips into a collective mode of vigilance and supplication.

This year's Suneung is a bumper cycle, driven by the unusually large cohort of students born in 2007 — the lunar-calendar "golden pig" year, believed to bring prosperity and luck.

That demographic bulge has swelled the senior class, sending candidate numbers up by more than 31,000 from last year. Retakers have also increased sharply as universities expand medical school quotas, intensifying competition across the board.

According to Jongro Academy, the nationwide competition rate for early admissions reached 9.77:1, up from 9.42:1 a year earlier. In the Seoul metropolitan area, the ratio soared to 18.83:1, while the Gyeongin region posted 13.08:1 and non-capital regions 6.49:1 — the sharpest jump outside Seoul in years.

The pressure does not end with a university acceptance letter.

South Korea has topped the OECD in university enrollment for 17 consecutive years; as of 2023, 70.6 percent of Koreans aged 25 to 34 held higher-education degrees, far above the OECD average of 48.4 percent.

With seven out of ten young Koreans college-educated, the race for a limited pool of stable, white-collar jobs becomes a zero-sum battle, driving up the number of young NEETs — those neither employed, in education, nor in training.

Statistics Korea's September employment data shows youth employment for ages 15 to 29 falling to 45.1 percent, marking a 16-month decline. More than 400,000 young people now describe themselves as "just resting," effectively off the labor force.

Japan, by contrast, enrolls far fewer students in higher education — roughly in the 50 percent range — but posts a 98 percent employment rate for new graduates.

A Korea Development Institute report underscores the scale of the problem: while the working-age population in their 20s shrank 17 percent over the past two decades, the number of idle youths surged 64 percent, from 250,000 to 410,000. The share of 20s neither studying nor working has doubled, from 3.6 percent to 7.2 percent.

Another ranking Korea has long topped is its suicide rate.

The country recorded 29.1 suicides per 100,000 people in 2024 — the highest since 2011 — with an average of 40 lives lost each day.

Suicide is the leading cause of death among Koreans in their 20s. A Korea University medical team analyzing 100,000 suicide cases from 2013 to 2020 found that 22.5 percent stemmed from economic or occupational distress, underscoring the direct link between socioeconomic pressures and mental health.

Suneung marks a pivotal moment for today's young Koreans, but its symbolism now extends far beyond a single exam day. Korea must move beyond habitual ceremony and confront the deeper structural strains threatening the future of its youth.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.