SEOUL, November 12 (AJP) - Korea, under strong pressure from labor unions, is moving to extend the statutory retirement age to 65 as it enters a super-aged demographic structure, but the shift could strain public finances and the national pension system if it fails to draw voluntary participation from the private sector, responsible for most hiring.

Korea's two largest umbrella unions are urging the progressive government and ruling party to mandate a "blanket, unconditional extension to 65 without wage cuts" within the year.

The ruling Democratic Party has proposed raising the statutory retirement age gradually to 65 by 2033, in line with the scheduled rise in the national pension eligibility age.

Korea joined the ranks of "super-aged" societies last year, with people aged 65 and older accounting for more than 20 percent of the population. Although the legal retirement age is 60, the national pension does not begin paying benefits until age 63 — a threshold that will rise to 65 by 2033. The gap has left many seniors with insufficient income and pushed labor force participation among those 65 and older to 37.3 percent in 2023, the highest in the OECD. Korea also records the OECD's highest senior poverty and suicide rates.

Japan, which encountered rapid aging decades earlier, offers lessons on how to manage the transition. Tokyo began addressing the issue 25 years ago and provided companies with autonomy and time to adjust. The Japanese government implemented a 12-year grace period, first introducing retirement-age guidelines in 1986 as a "non-binding obligation" before making them legally enforceable in 1998. The same gradual approach applied to raising the effective retirement age to 65: in 2000, Japan revised the Act on Stabilization of Employment of Elderly Persons, requiring companies to "make efforts" to ensure employment until age 65.

If Korea implements its proposed legislation this year without similar staging, the Korea Enterprises Federation (KEF) warns that the benefits will accrue mainly to full-time workers at large firms and public institutions with strong unions. The business lobby estimates the additional annual employment cost at roughly 30 trillion won ($20.6 billion) — equivalent to hiring around 900,000 workers aged 25 to 29.

Moreover, only 21.8 percent of Korean workplaces currently operate under a mandatory retirement system, meaning gains would disproportionately flow to workers in big corporations and the public sector. This helps explain mounting opposition from younger job seekers.

Experience from the 2016 introduction of the current 60-year retirement age also suggests unintended consequences. According to the Bank of Korea, the policy increased employment among workers aged 55 to 59 by about 80,000 by 2024, but reduced employment among those aged 23 to 27 by 110,000. For every additional older worker retained, employment for young workers fell by 0.4 to 1.5.

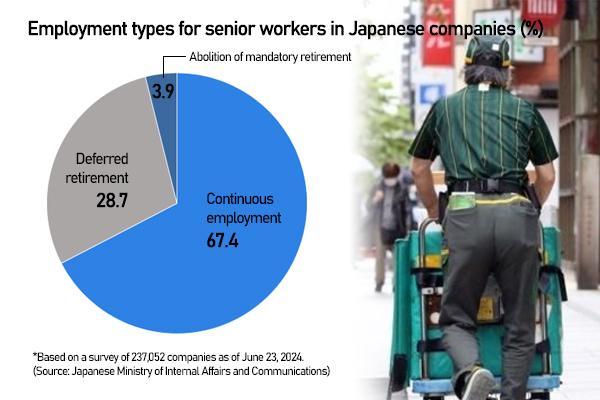

Japan's approach since 2006 gives companies three options: extend the retirement age, abolish retirement limits altogether, or provide continued employment for older workers under new contracts. As of April this year, companies must offer continued employment to anyone wishing to work until 65.

Under this system, employees formally retire at the designated age but are rehired with adjusted pay and conditions, allowing firms to retain experienced workers while managing labor costs.

Watami Co., which operates restaurant chains such as Subway and TGI Fridays in Japan, recently raised its retirement age to 65 and introduced a program enabling employees to work until 75. The move addresses both labor shortages and the desire of older workers to remain active.

As of June 2022, 99.9 percent of Japanese companies with 21 or more employees had adopted one of the three systems, effectively lifting the retirement age to 65 in practice, according to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. More than 65 percent of companies have either formally extended the retirement age or abolished it altogether.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.