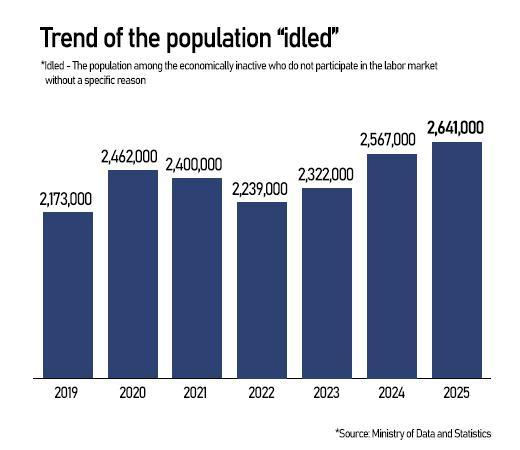

The share of university graduates among the unemployed reached 49.6 percent in September, up from 47.8 percent in 2024 and 37.7 percent in 2010, according to the Ministry of Data and Statistics.

The jobless rate among college or higher-degree holders has continued to climb despite a shrinking youth population and stable headline employment. Last month, there were only 0.42 job openings per job seeker—the lowest October figure since the 1998 Asian financial crisis. Registrations on the government’s Work24 platform fell 6.6 percent from a year earlier, while new job postings declined 19.2 percent.

Total employment in October increased slightly to 29 million, but the number of employed 15- to 29-year-olds plunged by 163,000, marking the 36th consecutive monthly fall. It now takes an average of 11.5 months for a young Korean to secure a first job—the longest delay on record.

Structural Mismatch in Economic Stagnation

Professor Lee Byoung-hoon of Chung-Ang University points to a structural imbalance between educational attainment and labor demand, a pattern increasingly seen across advanced economies.

“Most of today’s youth joblessness involves highly educated graduates,” he said. “Their numbers have surged, but labor market demand has not. Economic growth has become employment-poor; capital now flows into technology and automation rather than labor.”

Lee recommends that Korea benchmark the European Union’s “Youth Guarantee,” which treats unemployment not as a simple shortage of vacancies but as a breakdown in the school-to-work transition—a passage now prolonged and painful for many young adults.

“Policies that focus only on creating jobs, like temporary internships or short-term schemes, have limited impact,” he said.

“The Youth Guarantee approach recognizes that this is a structural transition issue. Governments must support young people’s entire journey—housing, debt relief, mental health, and career counselling—so they can cross the bridge from education to work.”

Labor Market Rigidity and Risk Aversion

Kim Jin-young, economics professor at Korea University, blames Korea’s rigid, union-leaning labor laws for discouraging companies from hiring inexperienced workers.

“Because dismissing staff is difficult, firms become extremely cautious when recruiting,” he said. “They prefer experienced employees because it’s hard to gauge the ability of newcomers,” making market entry especially harsh for young job seekers.

Kim argues that greater flexibility—allowing easier movement for both employers and workers—would shorten the long and often hesitant job-matching process. “Workers should be able to move between roles until they find the right fit,” he said. “Right now, both sides feel locked in, leading to long, cautious job searches.”

International Pressures and AI Disruption

Nobel laureate David Card of UC Berkeley cited four global forces undermining Korea’s youth employment: “1) disruption caused by US tariffs and trade policy. 2) AI. AI is heavily disrupting some sectors that use a lot of entry level software development engineers. 3) Competition from China. 4) Supply imbalances… supply outpaced the growth in demand for these workers.”

Beyond Welfare: Building “Good Jobs”

For Yoon Hong-sik, professor of social welfare at Inha University, the crisis reveals a deeper flaw in Korea’s welfare and industrial model. “We once believed AI would only replace low- or mid-skill work, but it’s now hollowing out high-skilled roles too,” he said.

“University education must shift from functional training to cultivating creativity and critical thinking—skills machines cannot replicate.”

Yoon argues that welfare states should not only compensate the jobless but actively foster quality employment. “In Nordic countries, 25–30 percent of all workers are employed in the public sector, providing universal social services. Korea’s share is barely 8 percent,” he said. “We need two pillars: robust public-sector jobs that deliver care, housing, and education, and a vibrant private sector that builds on this human capital to create advanced service industries.”

Rethinking What Education Means

Marcus Alexander, professor at London Business School, says the takeaway for students is increasingly clear.

“Learning ‘facts’ is irrelevant; learning how to think effectively is more important than ever,” he said. “The critical issue is not about getting a degree but about what graduates actually learn from very different courses and institutions.”

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.