It plans to tackle the loosely defined "comprehensive wage" system, under which various allowances and overtime pay are bundled into an annual or monthly salary. The government aims to require employers to track actual working hours and compensate overtime strictly based on recorded time.

The move marks the first attempt to bring under statutory control a wage practice that has long been tolerated through court rulings rather than explicitly defined in labor law.

The comprehensive wage system largely exists for employer convenience, allowing a preset amount of overtime, night work and holiday pay to be included in monthly salaries when tracking actual hours is deemed difficult. The practice is not stipulated in the Labor Standards Act but has been permitted in limited cases through Supreme Court rulings dating back to the 1970s. The term itself became widely used in the 1990s and gradually spread as a common pay arrangement.

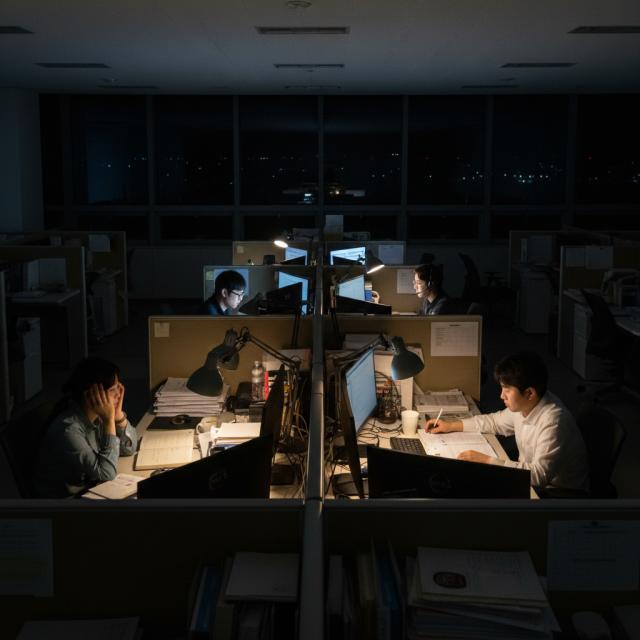

The system has been especially prevalent in sectors such as information technology (IT) and gaming, where long working hours are common. In practice, however, many companies have failed to pay additional compensation even when employees worked beyond the hours implicitly covered by their salaries, drawing criticism that the system has enabled unpaid overtime and wage violations.

Labor experts say the controversy stems from a gap between the law's wording and how it has been enforced. The Labor Standards Act requires employment contracts to clearly specify both wages and agreed working hours, defined as the hours set within statutory limits by agreement between employers and workers.

"If the law is interpreted literally, comprehensive wage arrangements are fundamentally inconsistent with this framework," said Jung Bong-soo, a labor attorney at KangNam Labor Law Firm. He added that in reality, many white-collar workers have a fixed number of overtime hours — such as 20 or 24 hours per month — vaguely included in their salaries, with no additional pay even when they work longer. "Strictly speaking, most of these practices amount to violations of the law," he said.

To address the issue, the government plans to require employers to guarantee full pay even when workers perform fewer hours than agreed, while mandating additional compensation for any work exceeding the agreed hours. As a core measure, all companies would be required to record actual working hours for overtime, night and holiday work.

Wage ledgers would have to include detailed information on working days and overtime hours, institutionalizing transparent tracking and management of working time. The Ministry of Employment and Labor said it intends to make clock-out records mandatory for overtime work across all businesses, with detailed requirements to be laid out in forthcoming legislation.

The legal package is also expected to include a provision prohibiting after-work text orders. Korea currently has no explicit rules governing after-hours contact, with disputes handled indirectly under workplace harassment or overtime regulations.

Some labor scholars caution that stronger enforcement will be crucial if the reforms are to have any real impact. "Supervision of working hours has been weak due to limited administrative capacity," said Kim Sung-hee, a professor at Korea University's Graduate School of Labor Studies. "Without clear, binding rules on how and when the measures apply, recommendations alone will not bring about change."

Labor attorney Jung also noted that South Korea already has a legally defined "discretionary work system" for jobs where working time is genuinely difficult to measure. Expanding its application in line with industry characteristics and job roles could help reduce confusion surrounding comprehensive wage practices.

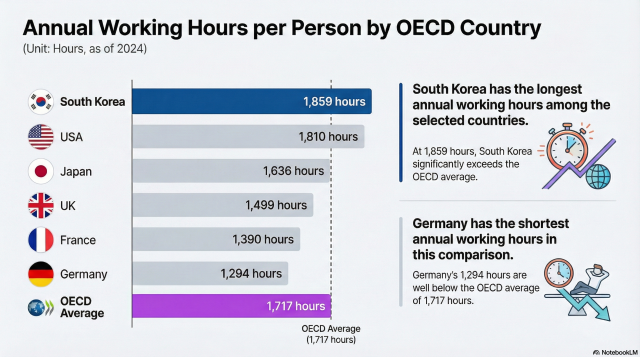

South Korea continues to rank among the countries with the longest working hours in the developed world. According to OECD data cited by the government, annual working hours stood at 1,859 last year, compared with an OECD average of 1,708. Although the figure has declined from 2,071 hours in 2015, South Korea still ranks near the top among member countries.

Countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark and France report fewer than 1,500 working hours per year, while the United States — the next highest among major economies — stands at around 1,810 hours. The government says its latest measures are aimed at narrowing that gap by making long hours more visible — and more costly — for employers.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.