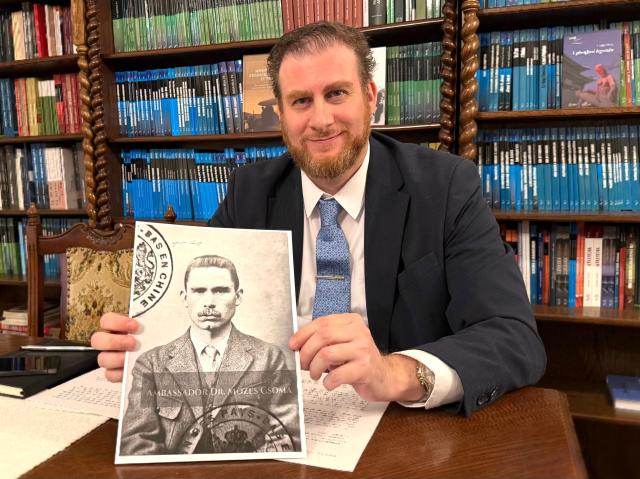

SEOUL, October 27 (AJP) - A Western engineer aiding Korean independence fighters in assembling bombs against imperial Japan sounds like a scene from historical fiction. But former Hungarian ambassador to South Korea Mózes Csoma found that it was real — and is preparing a book on the remarkable story of a Hungarian who joined Korea’s struggle for independence.

"As a historian, I find deep meaning in the story of someone who fought for another people’s freedom," said Csoma, now dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences and head of Korean Studies at Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary. "It is symbolic and meaningful that a Hungarian once helped Korea in its fight for independence."

Csoma, who had long studied Korean studies, founded Hungary’s first Department of Korean Studies at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) in 2008 before becoming Hungary’s ambassador to South Korea in 2018. After completing his term, he established another Korean Studies program at Károli University.

"About ten years ago, while researching North Korean students who studied in Hungary in the 1950s, I found a fascinating record," he recalled. "Some of those students who studied in Hungary after the Korean War helped Hungarian university students during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. They had wartime experience and taught locals how to handle weapons."

That discovery inspired him to explore deeper historical ties between the two nations. His research soon focused on Magyar — a mysterious Hungarian volunteer believed to have joined Korean independence fighters in China during the 1920s. Magyar’s name appears in several documents and cultural references, sparking debate over whether he was a real person or a fictional symbol of solidarity.

The figure even appears briefly in Kim Jee-woon’s 2016 film 'The Age of Shadows,' portrayed as a foreign engineer and skilled bomb maker aiding the Korean resistance. Though long assumed to be a fictional homage, Csoma's research suggests the character was based on a real historical figure.

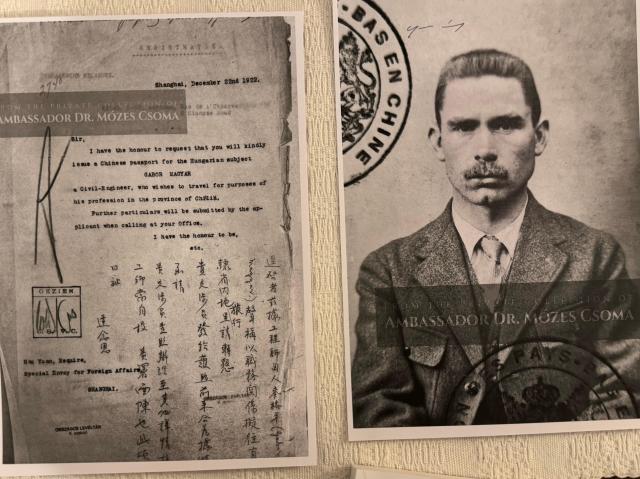

"'Magyar' normally refers to 'Hungarian,' but it is also a common Hungarian surname, so I began to suspect it was actually the name of a real person," Csoma said. "While reviewing Hungarian archives, I found records of a man named Gábor József Magyar that perfectly matched Magyar's story — that was the decisive clue."

One of the earliest written references to Magyar appears in Yaksan and the Uiyeoldan (1947) by modernist writer and independence activist Park Tae-won, which became a key source in confirming Magyar's existence. By tracing his travel routes from Mongolia to Beijing and Shanghai, Csoma found records that align with the 1923 Jongno bombing incident — one of the most significant attacks carried out by Korean independence fighters.

"I later found an original document showing that he returned from China to Mongolia, an unusual move for a war prisoner," Csoma said. "There are also records suggesting he traveled with independence activist Lee Tae-jun, implying he may have gone back to assist him."

His forthcoming book will also unveil new findings about Magyar's later life — not directly tied to Korea's independence struggle but revealing the arc of a man whose life bridged continents and causes.

Csoma's own path to Korea began with curiosity. "Korea's history impressed me deeply," he said.

Like Hungary, it has existed between powerful neighbors yet managed to preserve its sovereignty and identity."

He began studying Korean under Professor Gábor Osváth, who had studied in North Korea in the 1970s. "My first Korean teacher spoke with a North Korean accent," Csoma said, smiling. "So naturally, I learned Korean that way too."

Beyond his historical work, Csoma is regarded as one of Europe's leading scholars on North Korea. During his ambassadorship, he was also accredited to Pyongyang and visited the North four times. "The social atmosphere in North Korea reminded me of Romania under Nicolae Ceaușescu, where I once traveled with my family in the 1980s — strong control, personality cult, a closed economy," he said. "Because of that, North Korea didn't feel unfamiliar to me."

He recalled presenting his diplomatic credentials in 2019 to Kim Yong-nam, then President of the Presidium of the Supreme People's Assembly. "At the end of one meeting, a North Korean official smiled and said, 'Comrade Ambassador, your Korean is excellent — but not quite our Korean. Next time, please learn our version and teach it to the South Koreans.' It made me laugh," Csoma said.

When asked about access to research materials, he admitted it remains difficult. "Official archives in North Korea are closed, and many records have disappeared. Ironically, South Korea now holds more material on the North than the country itself," he said.

Having studied both Koreas, Csoma sees similarities beneath the division. "The systems are different, but the people are the same," he said. "Their tone, gestures, humor — they overlap. Talking with people in Pyongyang sometimes felt like talking to South Koreans."

The Department of Korean Studies he leads is expanding quickly — from 40 students at its launch in May 2023 to around 80 today, with its first graduates expected in 2027. Csoma teaches courses on topics such as comparative popular culture of North and South Korea in the 20th century, exploring films, music, and television as reflections of shared history.

He plans to establish a master's program in Korean Studies by 2027 and turn Károli University into a leading hub for Korean studies in Central Europe. "That is my mission," he said. "By combining my experience as a diplomat and scholar," Csoma said, "I hope to deepen the friendship between our nations — and help future generations build on it."

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.