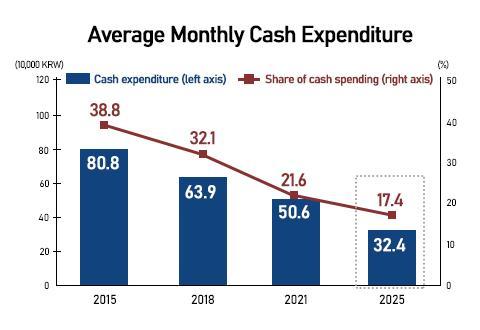

This year, individuals spent an average of 324,000 won ($226) a month in cash, less than half the 808,000 won recorded a decade ago, according to the Bank of Korea (BOK). Cash now accounts for just 17.4 percent of monthly spending, down from 21.6 percent four years earlier.

According to the National Information Society Agency, the number of kiosks nationwide surged from 210,033 in 2021 to 536,602 in 2023 — an increase of more than 300,000 units in just three years. Most cafés in central Seoul now operate two to three kiosks, while fast-food outlets often have five or more.

"I don't carry a wallet anymore," said Kim Sang-deuk, a 57-year-old office worker. "Everything works with Samsung Pay, so there's no need for cash."

Coins quietly disappearing

Physical currency, especially coins, is steadily vanishing from everyday use. This year, the BOK for the first time placed no orders for new circulation coins with the Korea Minting and Security Printing Corp., reflecting sharply declining demand.

Traditionally, the central bank forecasts annual demand by denomination and orders coins for both circulation and commemorative use. The absence of any circulation order underscores how rarely coins are now used in daily transactions.

"Coffee costs 4,500 or 6,700 won, and there's nowhere to put the change," said Lee Sung-jin, a 28-year-old office worker. "It's just easier to pay by card."

Yet the shift toward a cashless economy is uneven. Older people and low-income households remain far more dependent on cash.

People aged 70 and older still use cash for 32.4 percent of their spending, while households earning less than 1 million won a month rely on cash for 59.4 percent of expenditures, according to the BOK.

As South Korea enters a super-aged society — with those aged 65 and older now accounting for more than 20 percent of the population — the idea of going fully cashless remains contentious. A recent survey found that 45.8 percent of respondents oppose a cashless society, while only 17.7 percent support it. The most common concern, cited by 39.1 percent, was the risk of excluding financially vulnerable groups.

The challenge is visible on the ground. At a café in central Seoul, a foreign customer and a middle-aged woman struggled for several minutes to place orders at a kiosk, eventually requiring staff assistance.

"It's become too troublesome just to eat out," the woman said afterward.

A growing digital divide

A 2023 survey by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs found that only about 18 percent of older adults were able to place orders independently using kiosks. In practice, more than eight in ten elderly people experience difficulty using such machines.

Experts say the problem lies not only in digital literacy but also in design.

"Kiosks are designed from the supplier's perspective, not the consumer's," said Hur Jun-soo, a professor at Soongsil University's School of Social Welfare. "The icons, fonts and interfaces are not tailored to older users."

Hur added that although digital education programs for seniors have expanded, they often fail to reach people where help is most needed.

"Support should go beyond senior welfare centers and community halls," he said. "It needs to extend to the places where older people actually live and carry out their daily activities."

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.