Nearly a year has passed since Jeju Air Flight 2216, a Boeing 737-800 arriving from Bangkok, skidded off the runway during an emergency landing and slammed into a concrete embankment at Muan Airport in South Jeolla Province on Dec. 29, 2024. Of the 181 people on board, 179 were killed, with only two flight attendants surviving.

The aircraft attempted an emergency landing after an engine failure caused by a bird strike, according to preliminary findings. Yet for bereaved families, answers have remained scarce in the months since.

Presidential apology, lingering questions

President Lee Jae Myung, on his first day back at Cheong Wa Dae, issued a formal apology to the victims’ families, calling the tragedy a failure of the state’s duty to protect lives.

“As president, responsible for the safety of the people, I extend my deepest apologies,” Lee said, pledging to ensure accountability and prevent a recurrence. “The least we can do is make sure such a tragedy never happens again.”

The Muan crash marked the deadliest aviation accident in South Korea’s history, surpassing the 1993 Asiana Airlines crash in Haenam that killed 66 people.

Dispute over legal responsibility

Whether the Serious Accidents Punishment Act applies has emerged as a central legal fault line. Its application would determine not only criminal liability for senior officials but also whether families could receive compensation of up to five times the standard level.

Police are reportedly leaning toward concluding that the law does not apply — a stance that has alarmed victims’ families.

Moon Yoo-jin, a former judge and legal scholar, argues otherwise, saying the crash should fall under the law because it involved defects in public transportation facilities.

“An accident occurring during takeoff or landing, linked to a structure such as the embankment, can reasonably be viewed as resulting from defects in design, installation or management,” she said.

Conflicting findings and withheld disclosures

Shortly after the crash, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport said the concrete embankment supporting the airport’s localizer met regulatory standards. Subsequent reviews by other institutions contradicted that assessment.

The National Forensic Service later found that the structure violated both domestic and international aviation safety standards, a conclusion echoed by the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission.

Tensions deepened when the Aviation and Railway Accident Investigation Board (ARAIB) canceled a planned July briefing on its engine analysis after objections from victims’ families. The draft findings reportedly suggested that although the right engine suffered severe damage, the pilot had shut down the left engine — a claim families strongly disputed.

Families accused investigators of relying too heavily on analysis provided by the U.S. engine manufacturer while downplaying possible structural defects. Requests to access the full original engine analysis were denied.

A senior ARAIB official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the board had attempted to hold public hearings on Dec. 4 and 5 to present its findings, but was unable to proceed due to opposition from families. He added that earlier disclosure had been avoided because the investigation was still ongoing and premature release could have interfered with the process.

Safety upgrades lag behind promises

In the wake of the disaster, the transport ministry conducted a nationwide inspection of airport navigation facilities. On Jan. 13, 2025, it announced that nine azimuth structures at seven airports — Gwangju, Muan, Yeosu, Gimhae, Sacheon, Jeju and Pohang-Gyeongju — required safety upgrades.

As of Dec. 18, 2025, only Gwangju and Pohang-Gyeongju had completed the improvements. A ministry official said four additional sites had since finished work and that all nine would be upgraded by next year.

Lawmakers have criticized the pace of reform. Min Hong-chul, a Democratic Party member of the National Assembly’s Land, Infrastructure and Transport Committee, said repeated tragedies — from the 2014 Sewol ferry sinking to the 2022 Itaewon crowd crush — show a pattern of delayed accountability.

“Investigations must be swift and transparent, with the participation of bereaved families,” Min said. “Moving the Aviation and Railway Accident Investigation Board under the Prime Minister’s Office would be a first step toward restoring trust and uncovering the truth.”

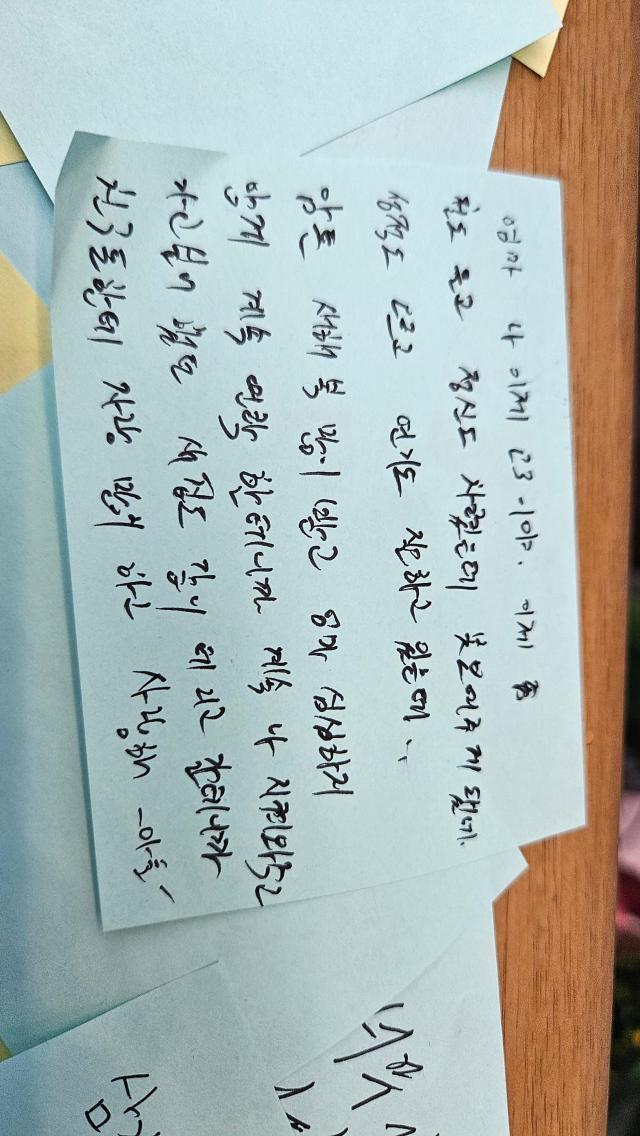

Nearly a year after the crash, messages of remembrance continue to line the walls of Muan Airport. For families, time has brought neither closure nor clarity — only a renewed call for accountability and structural reform.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.