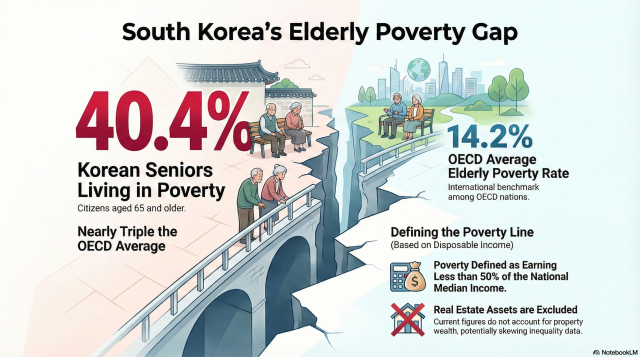

According to the OECD’s Pensions at a Glance 2023, four out of ten Koreans aged 65 and older live below the poverty line, defined as having an income at or below half of the national median disposable household income. The figure is nearly three times the OECD average of 14.2 percent. While the comparison is imperfect—Korea’s measure is income-based and excludes assets such as real estate—other global indicators consistently point to the same conclusion: old age in Korea is unusually harsh.

The burden grows heavier with age. Among people aged 75 and above, public transfers such as basic pensions do far less to reduce poverty than they do for younger seniors, suggesting widening disparities within the elderly population itself.

Structural features of Korea’s labor market compound the problem. Many older Koreans continue to work not by choice but by necessity, often in low-paid and unstable jobs. This year, the number of workers clocking fewer than 15 hours a week surpassed one million, with nearly 70 percent of them aged 60 or older. These “ultra-short-hour” jobs—typically in cleaning, waste collection or other manual tasks—offer little security and meager pay, trapping seniors in precarious livelihoods.

Health costs further magnify financial stress. Nearly half of Koreans aged 75 and above suffer from three or more chronic illnesses, and about 15.7 percent live with dementia—more than three times the rate among younger seniors. Medical and long-term care expenses hit the poorest hardest, often pushing them deeper into poverty late in life.

Gender disparities deepen the gap

Lifetime inequality in Korea’s labor market carries directly into old age, leaving elderly women especially vulnerable. In 2023, male workers earned an average of 26,042 won per hour, while women earned just 18,502 won—about 71 percent of men’s wages—according to the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. Nearly half of female workers were non-regular employees, compared with less than a third of men, and women were more than twice as likely to be classified as low-wage earners.

The retirement gap is stark. Men aged 60 to 64 receive an average national pension of about 980,000 won a month, while women receive just 460,000 won—less than half. OECD data show that 45.3 percent of elderly Korean women live in poverty, far above the OECD average of 10.2 percent.

“I come here every day for free meals”

The statistics take on human form at soup kitchens across Seoul. On a cold winter morning near Tapgol Park, dozens of elderly men and women gathered quietly before lunchtime, hands tucked into thin coats. For many, these soup kitchens are not only their main source of food, but also their only place of social contact.

An 88-year-old man originally from Hwanghae Province said he travels nearly an hour by subway each day to eat. “I come here for free meals every day,” he said. “Breakfast, lunch and dinner—I get them all from soup kitchens. There are others near Cheongnyangni and Seoul Station too.”

“Dentures are covered by insurance, but crowns are not. One tooth costs 500,000 to 600,000 won. I just can’t afford it.”

Another woman, 86, said she has no bathroom in her home. “I walk about five minutes to a public restroom,” she said. “It’s manageable most days, but in winter the roads freeze and I fall.” With no other work available, she collects cardboard, earning about 6,000 won a day if she is lucky. “I start at six in the morning and go until it’s dark.”

Volunteer Yoo Yoo-jae, 68, said around 300 elderly people visit the soup kitchen each day. “Some even come from Cheonan because subway rides are free,” he said. “Most are in their 70s or older. We have five people over 90 who come regularly, and about ten who use wheelchairs.”

A structural challenge, not a temporary one

“Suicide among older adults in South Korea has long been a chronic social problem,” said Kim Jae-woo, a sociology professor at Jeonbuk National University. As of 2023, the suicide rate for those aged 65 and above reached 40.6 per 100,000—about 1.5 times higher than the overall rate across all age groups.

“Economic hardship, physical illness, depression and social isolation all interact,” Kim said. “But poverty remains one of the most decisive factors.”

While expanding mental health services is important, Kim stressed that the solution must be broader. Korea, he said, needs stronger community-based care systems for frailty and chronic illness, more robust social networks, and—most critically—direct financial support for economically vulnerable seniors.

As policymakers debate reforms, the elderly lining up at Seoul’s free meal centers are already living with the consequences. Their hunger, illness and isolation are not abstract risks on a demographic chart, but daily realities unfolding quietly at the margins of one of the world’s richest economies.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.