A recent study by the Royal United Services Institute and the Open Source Centre estimated that Russian artillery accounts for roughly 70 percent of Ukrainian casualties. The Council on Foreign Relations similarly notes that artillery remains the “king of battle,” responsible for about 80 percent of casualties in the Russia-Ukraine war.

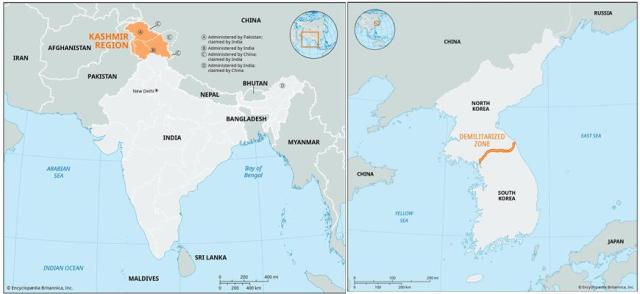

By that measure, India and South Korea stand among the world’s most capable conventional forces. In the 2026 rankings by Global Firepower, India and South Korea place fourth and fifth out of 145 countries — a rare pairing, reinforced by the fact that both remain de facto at war with hostile neighbors.

Beyond that similarity, their military profiles diverge sharply.

India is a nuclear-armed, all-volunteer force with one of the world’s largest standing armies. South Korea operates a conscription-based system built around a smaller active force and a massive reserve.

India spends about 2.3 percent of GDP on defence, roughly $74.4 billion in 2024, ranking near sixth globally in total outlays. Its army fields more than 4,000 tanks, centered on Russian-built T-90S and T-72 platforms and indigenous Arjun variants, and plans to acquire around 1,770 Future Ready Combat Vehicles. Much of this armour is concentrated along borders with China and Pakistan, reflecting the need to cover multiple fronts across a vast landmass.

South Korea, ranked fifth overall, devotes about 2.6 percent of GDP — around $43.9 billion — to defence. It maintains roughly 500,000 active-duty troops, backed by several million reservists. The army operates an estimated 2,300 to 2,500 tanks, mainly modern K1 and K2 Black Panther models, placing it among the few countries with more than 2,000 high-end main battle tanks.

In practice, India relies on mass — large numbers spread across immense territory — while South Korea concentrates dense mechanisation and firepower in a compact theatre.

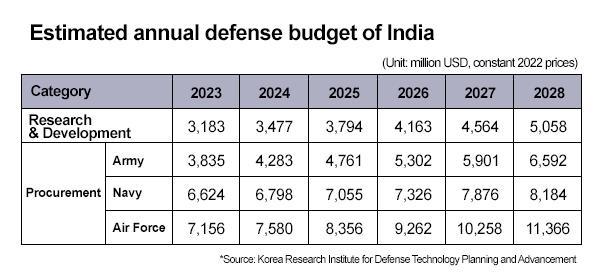

India has been steadily shifting defence investment toward air and sea power. In 2024, budget growth for the navy and air force — about 13 percent and 26 percent — outpaced the army’s roughly 11 percent increase, according to a Korea-based KIEP brief on India’s defence modernisation. The shift reflects recognition in New Delhi that land-based defences alone are insufficient under pressure from both China and Pakistan.

The Indian Air Force ranks sixth globally in the 2025 World Directory of Modern Military Aircraft. It fields about 1,716 active aircraft, with a balanced mix of fighters, helicopters and trainers. Its frontline fleet blends Russian Su-30MKIs, French Rafales and Mirage 2000s, and the indigenous Tejas, underscoring India’s reliance on multiple suppliers as it pursues stealth and next-generation programs.

South Korea’s air arm is smaller but more fighter-heavy. The Republic of Korea Air Force operates roughly 822 aircraft and ranks 12th in the same index. Fighters account for more than half its inventory, anchored by F-35A stealth jets, F-15Ks, KF-16s, FA-50s and the emerging KF-21 Boramae.

Geography shapes this structure. The ROKAF is optimized for air superiority and rapid strikes against North Korean artillery, missile and command targets, prioritizing high-end combat aircraft over large transport fleets. Its early adoption of fifth-generation fighters gives it an unusually dense concentration of advanced platforms.

At sea, South Korea holds a modest edge. Global naval rankings place the Republic of Korea Navy fifth, ahead of India’s seventh. Seoul operates a highly modernized fleet of Aegis destroyers, advanced frigates and Dosan Ahn Chang-ho–class submarines equipped with submarine-launched ballistic missiles.

India’s navy, by contrast, centers on two aircraft carriers — INS Vikramaditya and INS Vikrant — and Arihant-class nuclear ballistic missile submarines, making it the world’s sixth nuclear-armed submarine power. These assets support ambitions for expanded SSBN and SSN fleets. However, a significant portion of India’s surface fleet consists of older vessels facing modernization challenges, while South Korea’s smaller navy benefits from a higher share of recently built, domestically designed ships.

India’s defence market is shaped by its insistence on industrial self-reliance.

“Because India experienced decades of exploitation under colonial rule, there is a deep-rooted reluctance to depend purely on foreign imports,” said Jung Kyeong-woon, a research fellow at the Korea Association of Military Studies. “If you want to sell major systems to India today, the government expects you to bring factories, jobs and technology.”

The war in Ukraine has highlighted the risks of India’s long dependence on Russian weapons, from delays in S-400 deliveries to shortages of spare parts for Soviet-era platforms.

South Korea’s K9 Vajra programme illustrates how Seoul can adapt to this environment. A 2017 contract for 100 self-propelled howitzers, produced locally and delivered by 2021, was followed by a second order in 2024 for another 100 units through 2030. The programme combined competitive performance with domestic manufacturing — a model aligned with Make in India priorities.

Attention is now turning to whether the KF-21 Boramae, set to enter full service with the ROKAF, could become South Korea’s next major export platform for India.

Taken together, India and South Korea represent two of the world’s most formidable conventional military powers, built on different strategic logics but comparable industrial depth.

India brings scale, geographic reach and nuclear-backed deterrence. South Korea offers dense high-tech firepower, mature defence manufacturing and rapid production capacity.

As supply-chain security, localisation and interoperability gain importance, the overlap between the two systems is growing. For New Delhi, Korea offers a reliable partner less encumbered by geopolitical volatility than traditional suppliers. For Seoul, India represents one of the few markets large enough to sustain long-term defence-industrial cooperation.

Back to back in global rankings, the two countries now face a shared opportunity: to translate parallel strengths in conventional arms into a deeper strategic and industrial alliance.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.