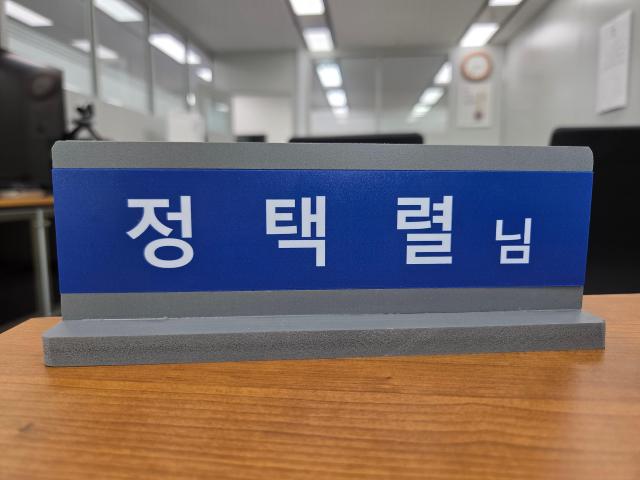

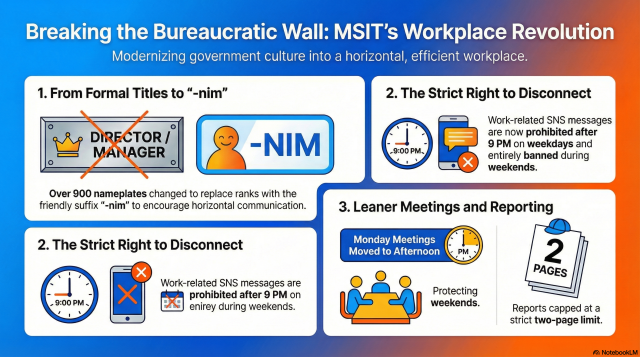

Last month, the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) replaced nameplates for more than 900 employees, removing official titles and leaving only first names followed by the universal honorific suffix “-nim.” The change cost about 10 million won ($6,900).

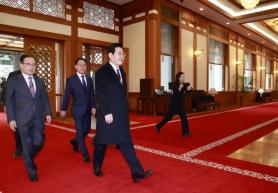

The move was ordered by Minister Bae Kyung-hoon, an AI engineer-turned policymaker who also serves as a deputy prime minister. Upon taking office in October, Bae asked ministry officials to abandon formal forms of address such as “deputy prime minister, sir.”

The unfamiliar shift became widely known during a televised briefing to the president, when a spokesperson referred to his boss simply as “Kyung-hoon-nim.”

Before entering government, Bae worked as a consultant for Naver and LG AI Research. He has sought to apply private-sector management practices to a ministry overseeing science and ICT — sectors where innovation and speed are critical.

A Gentler Atmosphere

At first, the change felt awkward. But officials say it has gradually softened the atmosphere inside the traditionally rigid bureaucracy.

“The organization feels gentler now,” said a director-level official. “We’ve started using colleagues’ first names — even those we worked with for years without ever calling them directly. It feels more personal.”

“I still feel awkward calling my superiors by their first names,” the official admitted.

As a compromise, some senior officials have encouraged juniors to use nicknames. First Vice Minister Koo Hyuk-chae, for example, is sometimes called “Ja-ryong-nim,” a reference to the legendary warrior Zhao Yun in Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

Efficiency Behind the Experiment

Officials say the initiative goes beyond symbolism.

“We’re trying to build respect and trust across ranks and improve efficiency,” said a deputy director-level official.

The title change has been accompanied by adjustments in daily work practices. After-hours and weekend messaging has been restricted. Monday meetings were moved from mornings to afternoons to ease post-weekend workloads. Briefing materials are now limited to one page.

In government offices, organizational charts typically run from “sajang-nim” (CEO) down to junior staff, and using first names for superiors has long been taboo – practice reinforced under Japanese colonial and military governments in modern history.

The removal of titles and the use of the universal honorific “-nim” to show respect for all employees, regardless of status, has long been common in the private sector.

Younger employees have largely welcomed the change, while older officials and academics have expressed reservations.

Jo Kyung-ho, a professor at Kukmin University, said the move could help modernize public administration.

“Korea’s civil service has developed closed, class-like structures,” he said. “Changing titles can be a starting point for cultural reform and more field-oriented governance.”

Yoo Sang-yeop of Yonsei University emphasized the distinction between authority and authoritarianism.

“Cultures change slowly,” he said. “Small adjustments like this can gradually erode rigid hierarchies, like water wearing down rock. But de-bureaucratization carries risks, since conservatism also protects public value where failure is costly.”

Ki Jung-hoon of Myongji University noted that bureaucratic caution stems from accountability and institutional rules, not just habit.

“Korea’s context differs from individualistic Western societies,” he said. “Hierarchy is embedded in governance structures.”

What matters are results, not rhetoric, observers all agree.

“Dropping titles is only meaningful if it leads to improvements in appointments, evaluations and decision-making,” said Rho Seung-yong, a professor at Seoul Women’s University’s Department of Public Administration. “De-bureaucratization cannot be achieved through symbolic gestures alone.”

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.