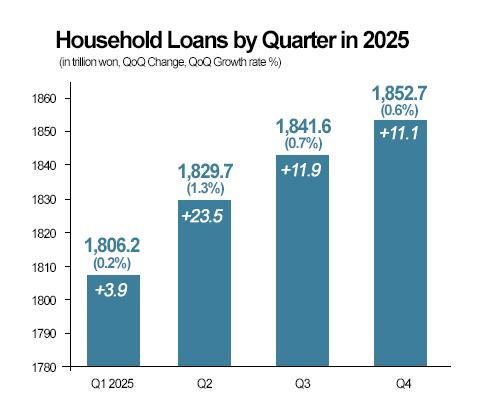

According to the Bank of Korea, total household credit outstanding stood at 1,978.8 trillion won ($1.37 trillion) at the end of the fourth quarter of 2025, up 14 trillion won from the previous quarter. It marked the highest level since data collection began in the fourth quarter of 2002.

For the full year, household debt expanded by 56.1 trillion won, or 2.9 percent, the largest year-on-year increase since 2021.

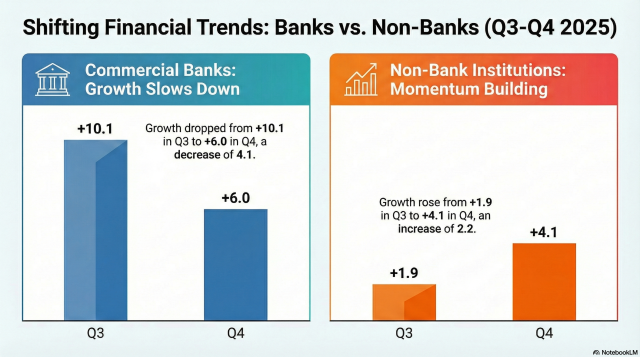

Loans from commercial banks rose by 6 trillion won in the fourth quarter, sharply easing from a 10.1 trillion won gain in the third quarter, as banks tightened lending to meet year-end regulatory caps.

By contrast, lending by non-bank depository institutions increased by 4.1 trillion won, more than double the 2 trillion won rise recorded in the previous quarter.

Within this sector, mortgage loans jumped by 6.5 trillion won, reflecting an influx of borrowers turned away by major commercial banks.

“Other loans,” including personal credit lines and non-mortgage borrowing, added 3.8 trillion won. These loans, often linked to equity market trading, pushed the balance of credit used for leveraged investment to around 27 trillion won toward the end of the year.

Within this category, non-mortgage loans increased by 5.1 trillion won to 260.4 trillion won, offsetting a decline in housing-related lending.

“This appears to be a temporary migration as commercial banks managed loan caps toward the end of the year,” said Lee Hye-young, head of the BOK’s Monetary and Financial Statistics Team.

She played down concerns over a long-term deterioration in debt quality, noting that a similar pattern was observed in the fourth quarter of 2024, when non-bank lending surged by 6.6 trillion won after a decline in the previous quarter.

Despite the move, critics argue that the impact on overall loan growth was limited, pointing out that the quarterly increase in personal credit loans fell by only 900 billion won from the third quarter.

Lee rejected claims that the regulations had failed.

“While growth in insurance company loans and card loans partly offset the decline in mortgages, the purposes of these loans vary, including stock investment,” she said.

She added that changes in lending patterns should not be interpreted as evidence of regulatory weakness.

The central bank projects that South Korea’s household debt-to-GDP ratio will decline slightly from 2024 levels.

“We will have a clearer picture after checking nominal GDP statistics in March and flow-of-funds data in April,” Lee said, adding that current indicators suggest the ratio will fall below the 89.6 percent recorded in 2024.

However, she cautioned that uncertainty remains high, given fluctuations in mortgage lending and credit-based investment.

“It is still too early to draw firm conclusions,” she said, citing volatility in housing finance and leveraged trading demand.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.