Samsung, SK, Hyundai Motor and LG aren’t just South Korean brands anymore; they’re global fixtures, as ubiquitous as fast Wi-Fi and K-dramas on long-haul flights. There are few corners of the world where someone hasn’t heard of South Korea. In cultural visibility, the last decade has felt as dizzying as the old Han River Miracle — a second, soft-power-driven version.

The artificial intelligence boom literally cannot operate without Korean memory chips. K-pop is sung, danced, copied, envied and, in equal measure, admired from São Paulo to Stockholm. K-dramas routinely sit atop global streaming charts. Streets in Seoul no longer look like tourist sites in a single country but like a sampling of the entire human palette. The country now boasts a Nobel literature laureate, Oscar winners and—judging from the nomination chatter—possibly a Grammy next year.

Even Google’s search rankings reflect the moment: K-pop Demon Hunters, a whimsical mash-up of Korean tradition, modern culture and idol fantasy, landed at No. 2 in global searches this year.

And the stock market? The Kospi has nearly doubled from its 1,961 close in 2015 to above 4,000 this year.

By all outward appearances, the country is soaring.

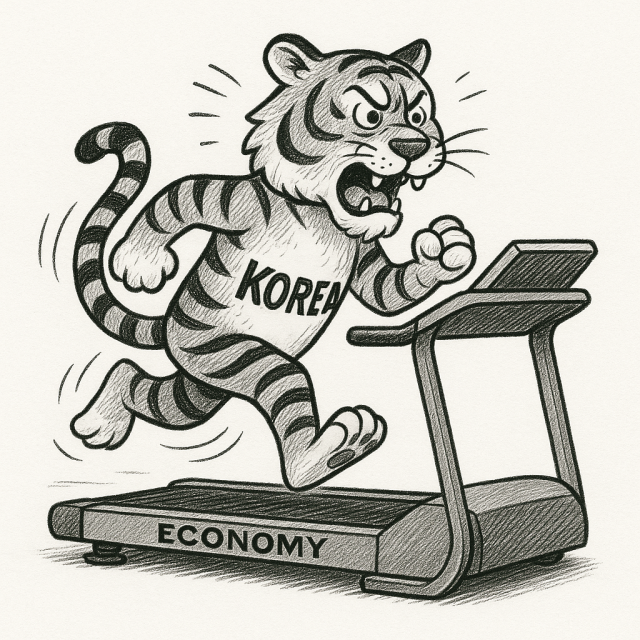

Except for one problem: strip away the shiny names and South Korea looks like a nation running on a treadmill. Lots of motion, not enough movement.

In just ten years, Korea has had four presidents—not two—because two were impeached along the way. The potential growth rate has withered from 3.3 percent in 2014 to under 2 percent today. The economy grew 2.8 percent in 2015; this year it will limp in at around 1 percent.

GDP per capita is stuck in time. Korea has wandered in the $30,000 range for more than a decade. This year’s estimate — $37,430 — puts the country behind Taiwan at $38,066. It is a far cry from projections made in 2015, when Hyundai Research Institute imagined a best-case scenario of hitting $50,000 by 2024. Even their worst-case forecast of 2030 now looks oddly optimistic.

Much of this stagnation is tied to the currency. While the Taiwanese dollar has been steady at around 30 per U.S. dollar for a decade, the Korean won has plunged from 1,100 to about 1,480. Had the won remained stable, Korea might already be celebrating the $50,000 milestone.

Some critics say the culprit is Korea’s “America habit”—the outsized investment its corporations, pension funds and individuals make in the United States. And the numbers do tell a story.

Koreans spent a record $5.93 billion abroad on credit cards in the third quarter. Foreign visitors in Korea spent just $3.76 billion — barely half. Outbound travel hit 7 million people. The travel account logged yet another deficit, because Koreans spend abroad far more enthusiastically than foreigners spend here.

Why? Because, as one economist put it, “Korea is expensive.” Official inflation may be 2 percent, but real inflation—when housing is included—feels above 4 percent.

The appetite for global assets is even starker. Koreans poured $99.8 billion into overseas securities this year — more than triple the foreign money coming into Korea. The country’s net external financial assets grew from $12.7 billion in 2014 to over $1 trillion today. The National Pension Service (NPS) alone holds 580 trillion won abroad.

“Seohak ant” retail traders, once a quirky niche, are now a force. Korean corporations are investing record amounts overseas. And the NPS — now the world’s third-largest pension fund — has become such a whale in global markets that policymakers have informally asked it to help stabilize the won.

But here is the uncomfortable truth: money follows returns. Koreans invest abroad because the returns look better there than at home.

Which leads to the real issue — not outbound investment but domestic weakness.

If a country wants people to study, invest, spend, build, visit and live here, it needs fundamentals that reward those choices. And Korea’s fundamentals have been eroding. The institutions feel fragile. The politics feel turbulent. The demographic outlook feels claustrophobic. And the economic model that powered the last 40 years is now more exhausted than triumphant.

A strong currency, a high per-capita income, a magnetic society — these don’t emerge by accident. They come from confidence, predictability, openness, and an economy that feels full of promise rather than boxed-in limits.

Without a broad, structural overhaul — one that tackles demographics, service-sector rigidity, education bottlenecks, regulatory clutter and the overcentralized political system — Korea risks becoming a country that is globally famous but internally stalled.

And if nothing changes, hitting $50,000 per capita won’t be a milestone.

It will remain a beautifully constructed dream — one that fades the moment you step off the treadmill.

The author is the managing editor of AJP.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.