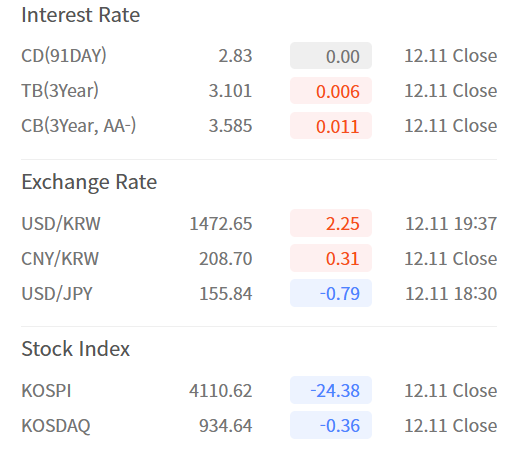

The Federal Reserve has cut its rate target range again this week, but the news barely rippled across Korean markets. The dollar strengthened, Korean stocks softened and yields inched upward — hardly the reaction one expects after a major policy decision from Washington.

That muted response reflected an important shift in global finance: the Fed may still set the rhythm, but it no longer commands the stage. Markets registered the U.S. rate cut and immediately turned their gaze to Japan, where far more consequential changes are brewing.

For more than a decade, investors have been conditioned to read every signal from the Fed as a defining market event. This time, they moved on. And they were right to.

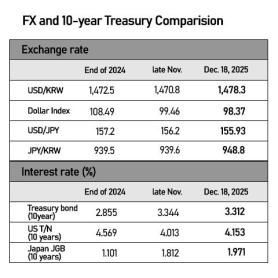

The Fed’s third consecutive cut — bringing the policy range to 3.50–3.75 percent — was fully anticipated and delivered with unmistakable caution. This was not a return to accommodative policy; it was a technical adjustment in an environment where the Fed’s room for maneuver is limited. The narrowing of the U.S.–Korea rate gap may ease some pressure on the won, but it won’t reverse the powerful outward flow of Korean capital into global markets. Nor does it free the Bank of Korea from its domestic constraints, including a housing market sensitive to any hint of loosening.

Simply put, the U.S. rate cut has already played its part. The story now moves elsewhere.

Japan’s Shift Is the Real Disruptive Forc

Japan, long the quiet spectator in global monetary dynamics, is suddenly the decisive variable. After decades of anchoring global liquidity with near-zero rates, the Bank of Japan is edging toward normalization. Even a modest rate hike — a move unremarkable in most economies — would send tremors through the global financial system.

That is because the yen carry trade is not a niche strategy; it is a structural pillar of global liquidity. Trillions of dollars in positions worldwide have been built on the assumption that Japanese money will remain cheap, the yen will stay weak and volatility will remain low. These conditions are evaporating. Japan’s 10-year government yield has been pressing toward multi-decade highs, speculative yen shorts are stretched and the currency is no longer one-directional.

Markets know the implications. Every major episode of global market stress over the last 25 years — from the 1998 Asian crisis to the 2008 collapse, to the 2015–16 turbulence and the early-2020 shock — involved a surge in the yen and a disorderly unwinding of leveraged positions. Japan’s normalization would not merely shift sentiment; it would reprice risk across every major asset class globally.

In that sense, the Bank of Japan’s next step is not a regional issue. It is the defining global risk of the coming year.

Korea Lies Directly on the Fault Line

Korea is one of the markets most exposed to this shift — not because its fundamentals are weak, but because it sits at the intersection of global capital flows shaped by both the United States and Japan. A disorderly carry-trade unwind would push up volatility in the won, trigger foreign rebalancing and pressure both equities and bond yields.

But Korea also stands to benefit if it positions itself strategically. As rate differentials across the United States, Japan and Korea narrow, and as weaker emerging markets struggle with instability, Korea’s institutional credibility and relative resilience could enhance its standing as a safe regional alternative. The opportunity is real — but only if it is earned through preparation, not assumed by default.

Policy Must Catch Up With Reality

Korea’s macro playbook must evolve as the global axis of risk shifts.

First, monitoring Japan must become as central as tracking the Fed. The yen’s trajectory, Japanese government bond yields, shifts in speculative positioning — these are now core indicators, not peripheral curiosities.

Second, Seoul must treat interest rates, currencies and capital flows as an integrated system. Fragmented management will not withstand the level of volatility Japan could unleash.

Third, Korea must strengthen its market infrastructure. Thin liquidity in FX and derivatives markets amplifies shocks. That vulnerability is no longer tolerable.

Fourth, the country must communicate risk more directly to households and retail investors, whose aggressive overseas allocations have become a structural feature of the Korean market. The volatility ahead is not cyclical; it is systemic.

The U.S. rate cut may dominate headlines, but it is no longer the hinge on which the global financial system turns. Japan’s slow exit from ultra-loose monetary policy represents a far more consequential shift — one that could reshape liquidity, valuations and volatility across the world.

Korea does not get to choose whether this transformation happens. It only gets to choose how prepared it will be.

What is clear is that the axis of global financial risk has already begun to tilt.

It is no longer aligned solely with Washington. It is moving unmistakably toward Tokyo.

And Korea’s ability to navigate the next phase depends on how quickly it internalizes that change.

* The author is the managing editor of AJP.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.