SEOUL, Feb 19 (AJP) - Seoul has once again taken a hard-line approach to real estate policy — deploying higher taxes, stricter lending caps and strong-worded warnings from the president. Yet instead of cooling the market, the measures have fueled another surge in housing prices and rents in the capital.

Sound familiar?

Koreans have witnessed this cycle under almost every progressive government over the past two decades.

The pattern is repeated: authorities crack down on multi-home owners to suppress demand, while supply remains constrained and demand stays concentrated in Seoul. The result is the opposite of what policymakers intend.

According to the Korea Real Estate Board (REB), the average sale price of apartments in Seoul rose about 9 percent in 2025, the steepest increase since 2006, when prices surged nearly 20 percent.

Over the same period, Seoul’s price-to-income ratio (PIR) approached 14 based on median income. In practical terms, this means a household would need to save its entire income for more than 14 years — without spending a single won — to afford a home. Since PIR does not account for living expenses or widening income inequality, the actual burden is even heavier.

Regulatory tightening, limited impact

To rein in prices, the government has rolled out successive regulations.

On June 27 last year, mortgage loans in major regulated areas were capped at 600 million won ($440,000), and buyers were required to move in within six months. On Oct. 15, Seoul and major cities in Gyeonggi Province, including Suwon, Anyang and Gunpo, were designated as land-use permit zones, extending mortgage restrictions even to non-regulated areas.

Despite these interventions, prices have continued to climb.

Supply shortage meets excessive liquidity

Two essential conditions for stabilizing housing prices — expanding supply and absorbing excess liquidity — have remained unmet.

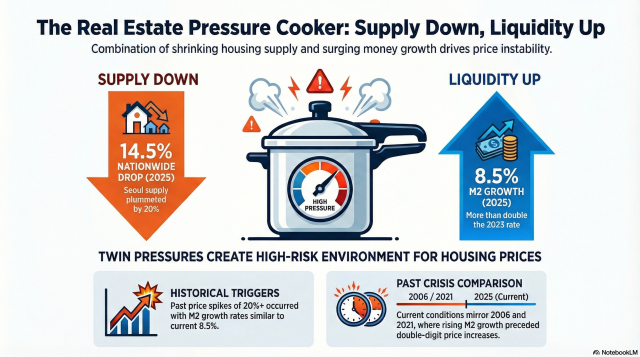

According to the Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS), nationwide housing supply in 2025 fell to about 380,000 units, down 14.5 percent from the previous year. In Seoul, supply dropped nearly 20 percent to 41,566 units from 51,452 in 2024.

While supply in 2025 was slightly higher than in 2023, the key difference was liquidity.

In 2023, M2 money supply growth stood at just 3.89 percent. By 2025, it had surged to 8.5 percent, more than doubling in two years. Liquidity was being injected into the market at a much faster pace.

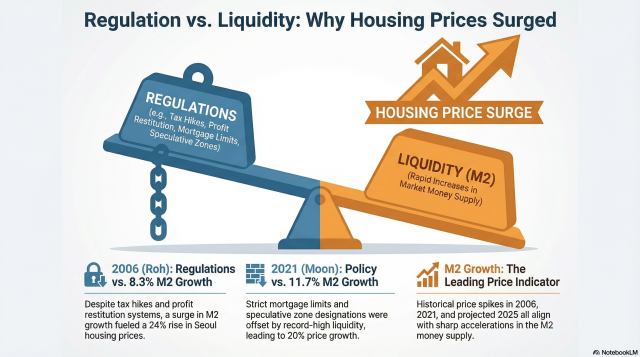

History shows that housing booms have consistently coincided with rising M2 growth. In 2006, when prices jumped about 24 percent, M2 growth reached 8.3 percent. In 2021, when prices rose nearly 20 percent, it climbed to 11.7 percent.

Similar regulatory regimes were in place at the time.

Under former President Roh Moo-hyun, the government strengthened comprehensive real estate taxes and introduced the reconstruction excess profit restitution system. During the Moon Jae-in administration, speculative zones and tighter mortgage limits became the policy centerpiece.

Abundant liquidity tends to push down interest rates and inflate asset prices. When strict regulations collide with shrinking supply, competition for remaining inventory intensifies, driving prices even higher.

Liquidity debate

After the Jan. 15 Monetary Policy Committee meeting, Bank of Korea Governor Rhee Chang-yong argued that M2 growth excluding securities was only 4.74 percent in 2025, saying the money supply had not increased significantly.

However, data suggests that a large portion of liquidity entered the housing market through stock gains.

According to documents submitted to Rep. Kim Jong-yang’s office on Feb. 10, more than 2 trillion won in stock profits was used for home purchases in the second half of last year alone. This weakens the rationale for excluding securities from liquidity assessments.

Need for liquidity management and tax reform

Financial authorities acknowledge the importance of liquidity control.

Explaining the rate freeze on Jan. 15, Rhee noted that “abundant liquidity acts as a driver for rising asset prices,” implicitly recognizing its role in real estate inflation.

Experts also warn that tax policies can backfire.

“Holding taxes can reinforce the perception of property as a premium asset, while high transaction taxes discourage selling,” said a real estate research institute official, adding that taxes ultimately become part of a home’s price tag.

Supply is key — but no quick fix

The most effective long-term solution remains boosting supply. On Jan. 29, the government announced plans to prioritize 60,000 units in Seoul and surrounding areas.

Yet few expect immediate relief.

“Construction will not begin until 2027 or 2028 at the earliest, so it will take time for supply to reach the market,” said Lee Chang-moo, a professor at Hanyang University. “These measures should be viewed from a mid- to long-term perspective.”

A similar lag occurred under the Roh administration, when new towns such as Pangyo, Dongtan and Gwanggyo were planned. Although roughly 300,000 units were announced, large-scale move-ins did not begin until 2009, after Roh left office.

Experts say today’s policies should be judged in the same way — not by short-term price movements, but by whether they ultimately correct the structural imbalance between supply, liquidity and demand.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.