SEOUL, February 10 (AJP) - The lightning sellout at the latest ticket opening for BTS’ two shows at London’s Tottenham Hotspur Stadium has become a familiar pattern across the global ticket window for the group’s first full seven-member world tour in nearly four years.

Both nights vanished within 30 minutes, filling a venue that holds roughly 62,000 people per concert almost instantly. Over two evenings, close to 120,000 fans are expected to pass through the gates. At this point, BTS’ touring operation has reached a scale where success is no longer event-driven, but structural.

Euphoria over a long-awaited comeback and the devotion of the fandom only partially explain the response—especially in a city that likes to remind visitors it is where pop music “began.” Fans agree the wait is worth it, and the reason, they say, lies not just in spectacle but in setlists.

Across more than a decade on the road, BTS have quietly turned the concert setlist into a repeatable system—one that evolved from improvisation to standardization, and then toward controlled flexibility. Tracing that arc shows how a group that once tested songs in small rooms came to command stadiums with industrial consistency.

The story begins far from London. BTS’ first full-scale tour, 2015 BTS LIVE TRILOGY: EPISODE II. THE RED BULLET, comprised just 12 shows. Even then, it was unusually ambitious, crossing four continents through Kuala Lumpur, Sydney, Melbourne, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Mexico City, São Paulo, Santiago, Bangkok and Hong Kong. The itinerary hinted early at a global ceiling far above typical rookie acts.

Those early setlists reflected the moment. Rather than leaning on chart dominance, the group built performances around identity. Songs such as “N.O,” “We Are Bulletproof Pt.2” and “No More Dream” opened shows, followed by “BTS Cypher Pt.2” and “Pt.3,” “If I Ruled the World” and “Paldo Gangsan.” The concerts were heavy on talk segments, light on spectacle and flexible night to night. The goal was not polish, but proof—testing which songs could survive outside the studio.

Two tracks that would later become staples, “Dope” and “I Need U,” first distinguished themselves in this environment. Long before they became statistical anchors of later tours, they proved durable in rooms where audience reaction could not be engineered.

Over time, those reactions accumulated into data. Aggregating setlists across BTS’ world tours shows that “Dope” has been performed 162 times, making it the most-played song in the group’s touring history. “Fire” follows with 137 performances, and “I Need U” with 130. These figures do not simply reflect popularity; they represent endurance—songs that deliver kinetic payoff across arenas and stadiums, languages and markets, regardless of context.

The first attempt to formalize that reliability came with the Love Yourself tour. Instead of rewriting shows city by city, BTS adopted a hybrid model. Most of the 24 to 27-song setlist remained fixed, while a five-song block was deliberately left open. In that rotating section, tracks such as “Boy In Luv,” “Fire,” “Dope” and “Blood Sweat & Tears” were swapped depending on region and response. The effect was subtle but consequential. Japanese shows leaned toward emotionally resonant mid-era tracks like “I Need U,” while U.S. and European dates favored high-impact performance pieces such as “Fire” and “MIC Drop.” Localization became strategy rather than instinct.

That experiment ended with Speak Yourself, BTS’ first full stadium tour. Here, flexibility gave way to uniformity. Every stop—Seoul, Paris or Los Angeles—featured essentially the same setlist, running about 24 songs from start to finish. Production cues, camera paths, pyrotechnics and pacing were locked. The concert was no longer modular but standardized, designed to deliver identical value at scale.

Only once did that standard break. At the final Seoul show, “IDOL” was inserted into the encore while “Run” was removed—the sole deviation across dozens of performances, a symbolic nod to the tour’s point of origin rather than a logistical shift.

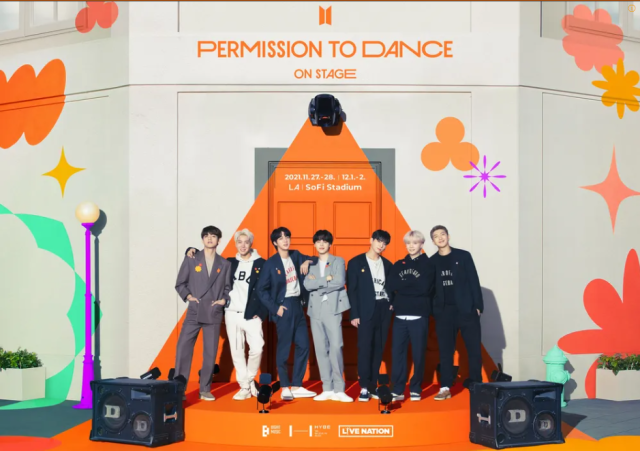

Crucially, collaboration entered the touring equation. In November 2021 at Los Angeles’ SoFi Stadium, Megan Thee Stallion appeared onstage for a live rendition of the “Butter” remix. At other dates, Coldplay’s Chris Martin joined for “My Universe.” These moments were not spontaneous detours; they were accommodated by design. The setlist had evolved from a fixed sequence into a system defined by function.

Seen in that light, the London sellout feels less like a milestone than an outcome. In Japan, BTS concerts continue to emphasize localized arrangements and emotional continuity. In North America and Europe, energy-forward tracks like “Dope” and “Fire” anchor the early stages of the show. Across Asia, choreography-driven numbers are paired with fan anthems to intensify collective response. The template adapts; the structure holds.

The contrast is stark. In 2015, BTS crossed four continents in 12 mid-sized shows, testing material in rooms that could not absorb error. A decade later, the same group fills a 62,000-seat stadium in London—twice—without altering the core mechanics of its performance model. The journey from small venues to stadiums was not propelled by viral moments alone, but by an increasingly precise understanding of how live music scales.

That understanding is embedded in the numbers. “Dope” at 162 performances, “Fire” at 137, “I Need U” at 130—figures that chart the quiet evolution of a touring system refined over years of iteration. BTS’ world tour is no longer a sequence of dates. It is an operational framework, tested in small rooms, validated on global stages and now capable of filling stadiums on demand.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.